The Death of Judas (Nos. 41-42)

This scene opens with the narration of how the High Priests and elders deliver Jesus to the governor of Judaea, Pontius Pilate. Judas sees this and feels remorseful, trying to give back the money they had given him. Choirs 1 and 2 together now impersonate the priests and elders and dismiss him abruptly. Judas throws the silver pieces into the temple and kills himself.

Two new solo roles (Priests I & II) have a short arioso where they state that they can’t put the money in the Temple treasury since it’s been tainted (“Blutgeld”, “blood money”).

This is followed by an energetic aria for the bass with a virtuoso violin solo, which seems right out of an Italian violin concerto. The high energy and broken melodic lines by the violin’s “bariolage” depict the disorientation and desperation of Judas, and its abrupt ending is consistent with his self-inflicted death. The text echoes Judas’ demand of the priests to get Jesus back in exchange for returning the money. The movement is set for Coro 2, consistent with the principle that this group receives the text that would go against the prophecies if it were fulfilled.

Matthew 27, 1-6

Pilate Questions Jesus (Nos. 43-44)

The next block of recitative covers two different topics. It first tells the story of what became of the “Blutgeld” (it was used to buy a potter’s field outside Jerusalem). Matthew refers this and quotes a prophecy from Jeremiah’s book.

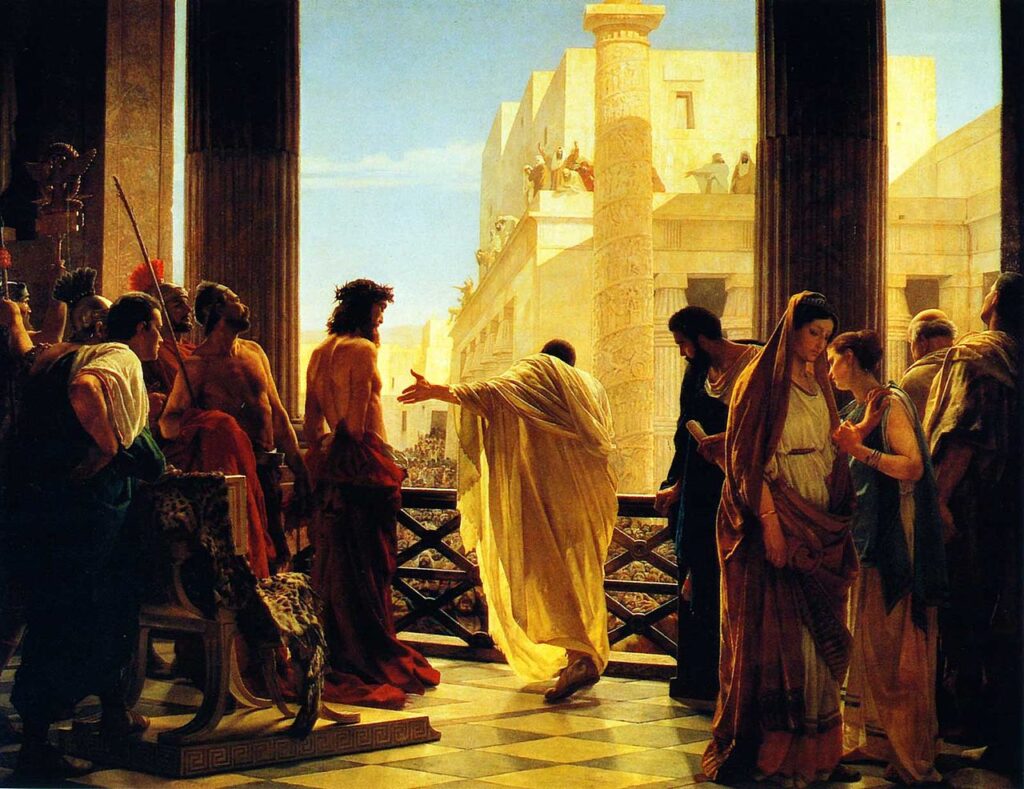

Then, the first direct exchange between Pilate and Jesus happens. Pilate asks Jesus whether he is the “King of the Jews” and then demands a reaction from Jesus to the accusations of the priests and elders, which Jesus doesn’t provide.

The Passion Chorale with melody by Hasse makes its third appearance, with a stanza of another Paul Gerhardt hymn encouraging the listeners to entrust their worries to “the most faithful care of him who governs Heaven”.

Matthew 27, 7-14

Jesus is Sentenced to Death and Mocked (Nos. 45-54)

The next scene, one of the most dramatic of the Passion, begins with the Evangelist narrating the custom of releasing a prisoner to the crowd at each feast. Pilates gives the choice to the crowd of releasing Barabbas or Jesus. At this point, Pilate’s wife makes a brief appearance to intercede in favor of Jesus. Pilate continues to dialog with the crowd whose screams are represented in several interventions of the choirs. The first one is the homophonic exclamation “Barabbas!”, and then their first clamor for Jesus’ crucifixion, in a fugato in which the two choirs sing together. As he does often, Bach illustrates the concept of the cross with the uncomfortable upward leap of an augmented fourth in all voices as they enter in succession.

At this point, Bach and Picander pause the action by interpolating the 4th stanza of Johann Heermann’s “Herzliebster Jesu” chorale in its third appearance. This stanza presents the image of the Good Shepherd suffering for his sheep – a way to remind the listener of the ultimate purpose of all this cruelty.

Pilate then asks, “What evil has he done?”, but Bach doesn’t let the mob answer right away. Rather, the soprano takes over in representation of the believer, with an arioso that answers Pilate’s question by enumerating all the good that Jesus has done (don’t miss the word-painting with the line going the highest for “He raised up those who are distressed”).

This arioso is followed by what is arguably the most beautiful aria in the entire Passion: “Aus Liebe” (“Out of love”) positioning Jesus’ sacrifice from the perspective of his love for us. No basso continuo – just two oboes da caccia supporting a weightless flute and the soprano voice in this welcome respite from the brutality of the scene.

In what John Butt calls “one of the most disturbing moments in the history of western music”, the beauty of the soprano aria is instantly erased by the next entry of the blood-thirsty mob. They don’t answer Pilate’s question – rather, they continue yelling for Jesus’ crucifixion with more upward fourths.

The Evangelist narrates how Pilate desists from trying to reason with the crowd and washes his hands. The mob’s response (“His blood be upon us and our children”) is set by Bach to a chorus with the two choirs merged, and a bass line that moves continuously in eighth notes over the busy vocal lines doubled by the orchestra. The effect is surprisingly effective at mimicking a disorganized, loud crowd.

The Evangelist states that Pilate releases Barabbas and hands over Jesus to be crucified.

It’s now the turn of the alto to impersonate the believer and ask for God’s mercy in another powerful arioso/aria pair. Since this text clamors for the executioners to stop, it’s set to Coro 2. The recitative, with the dotted rhythms in the strings and unstable harmonies, represents Jesus’ scourging. This device is very similar to what Handel would use (several years later) in the alto aria “He was despised” of his oratorio “Messiah”.

The dotted patterns, albeit in a slower figuration, continue into the aria (“Können Tränen meiner Wangen”), set in the sweet key of G minor. The poetry refers to the believer’s tears as a representation of Jesus’ bleeding from his wounds.

Next the Evangelist, in a very expressive recitative line, describes the mocking and flagellation of Jesus, with another illustration by the choirs yelling at him alternatively.

The scene ends with a chorale – a full two stanzas of the Passion Chorale in its fourth presentation. The verses reflect upon Jesus’ wounds, mockery and suffering, and end in a rhetorical question.

Matthew 27, 15-30