Christoph Graupner (1683 – 1760) studied music with Johann Kuhnau at the Thomasschule, and law at the university of Leipzig. His musical career, however, took him away from the city. By the early 1720s, he was firmly established at the Darmstadt court and he had built a reputation as Kapellmeister and prolific composer of cantatas, instrumental music, and opera. When Kuhnau died in 1722, the Leipzig city council considered Graupner as a strong candidate for the open Thomaskantor position and invited him to apply. Georg Philipp Telemann had already been offered the job and declined.

Graupner auditioned in early 1723 with two cantatas for the second Sunday after Epiphany, on January 17. The pieces were well received, and his reputation as an experienced Kapellmeister weighed in his favor. The city council offered him the position, seemingly securing a respected and well-qualified successor to Kuhnau. Graupner himself appeared open to the move; his application suggested that the Leipzig role could provide him with greater artistic independence than Darmstadt, where court finances were tight and opera had been discontinued.

Ultimately, however, Graupner could not accept the Leipzig job because his employer, Landgrave Ernst Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt, refused to release him from service. The Landgrave, recognizing Graupner’s value, increased his salary and secured his loyalty by guaranteeing his post for life. Graupner’s inability to take the position paved the way for Johann Sebastian Bach’s eventual appointment, an outcome to this saga that became pivotal to the history of music. When hearing the news of Bach’s engagement, Graupner wrote a letter to the city council providing an enthusiastic endorsement.

The cantata “Lobet den Herrn alle Heiden”, the second of Graupner’s audition pieces, intended to be performed after the sermon, was preserved in an autograph score and is catalogued as GWV 1113/23b. It’s richly scored for two trumpets, two oboes, timpani, strings, and continuo, plus a four-part choir and alto, tenor and bass soloists.

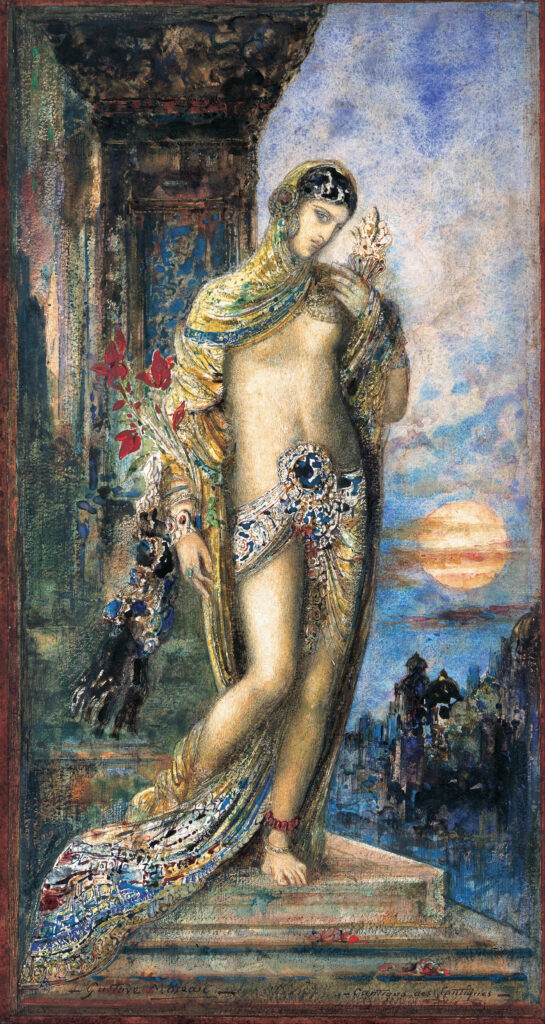

The libretto, by an unknown poet, opens with a biblical quote (the short Psalm 117) and closes with a stanza of “In allen meinen Taten”, a hymn by Paul Fleming of 1642. In the rest of the movements, the author reinterprets the story of the wedding at Cana (John 2: 1-11, Gospel reading for this Sunday), as the more general notion of the human soul searching for comfort in Jesus, employing the frequent metaphor of bride and groom rooted in the erotic poetry of the Song of Songs.

The cantata starts with a powerful setting of the Psalm text for the choir and the full orchestra, segmented into different sections. The initial meter is an animated 12/8, with the trumpets and timpani creating a jubilant and festive atmosphere. The brass fanfare is underscored by repeated notes and ascending arpeggios in oboes and strings, which leads to the homophonic entrance of the choir for the first line of text. The second verse shifts to a fugato, with a subject that starts on the bass line and rises up to tenors, altos and finally sopranos. For the mentions of mercy and truth, Graupner changes the mood radically – the meter shifts to binary, the tempo marking to “Largo”, and the text is delivered by alternating soloists and “tutti”. The strings interject comments in dotted rhythms, and the sound grows gradually towards an imposing chord on “Ewigkeit” (“eternity”). To close the movement, the “Hallelujah” is set as another fugato, back in a 12/8 meter. The main subject consists of rising eighth notes in groups of six, against a countersubject of descending long notes, both of which alternate among the different voices doubled by the instruments.

The next movement includes the only direct reference in the entire libretto to the Gospel of the day: “her water turns to wine”. “Shulamite” is an allusion to the bride in the Song of Songs (see Song 6:13), an image which is in turn connected to the idea of the believer’s soul’s, and the Church’s, loving relationship and intimacy with Christ. Musically, Graupner delivers a surprise in this movement. It opens as an “accompagnato” recitative for the alto, with strings and continuo, with melismas emphasizing key expressions such as “fest gläubt” (“firmly believe”), “große Lust” (“great delight”), and “Wasser” (“water”). However, when describing how Shulamite rests in the grace of her bridegroom’s bosom, he brings the full choir in, singing homophonically in long notes first (for the word “ruht”, “rest”), and in short bursts later for the rest of the verse, until the alto resumes the recitative by repeating the opening verse.

The following “da capo” aria for the alto is accompanied by strings (one violin and viola) and a solo oboe, supported by basso continuo. The text describes how a believer can trust in God’s almighty power and live free of worries. The “A” section has the violin in continued wide leap dotted motifs, possibly to reflect the care-free concept mentioned in the text. The melodic material presented in the voice is not anticipated in the instrumental ritornello, and it includes an extended melisma, and later a long held note, both on the word “Sorgen” (“worries”). The “B” section forgoes the dotted rhythms in favor of straight parallel eighths on the violin and oboe, which adorn a held note in the voice on the word “Allmacht” (“omnipotence”).

Next is a tenor “secco” recitative, in which the poet reflects on how the Holy Spirit can provide comfort to a discouraged soul, referred to again as Christ’s bride. The soul’s misplaced “trust in herself and her own strength” is contrasted to the “strength and life of the Supreme Spirit” which can provide true rest to the soul. The highest note of the vocal line is given to “Kraft” (“strength”).

The conflicting effects of fear and hope on the “worldly heart” is the topic of the next movement, an aria for tenor accompanied by two oboes, violin, viola and continuo. The idea of the scales “swaying” (“schwanket”) is illustrated with a long melisma in sixteenth notes. In the “B” section, Graupner employs “bassetto” (i.e. leaving out the basso continuo and giving the lowest notes of the harmony to the upper strings instead) to represent fear (“Furcht”), until hope is mentioned (“Hoffnung”) in a melisma supported by rising notes on the basso continuo.

The bass gets the following recitative, this time “accompagnato” with strings (two violins and viola). After the first statement reiterating some of the previous ideas about Jesus protecting the believer in a cruel world, the writing changes to Arioso, to emphasize the final exhortation to receive the “highest good” – Christ himself, thus closing the libretto’s rhetorical arc.

The final chorale, wisely chosen to underline the overall message of the libretto, is presented homophonically by the choir within an elaborate setting for the full orchestra, in a triple, dance-like meter. The orchestra opens with an eight-bar introduction and then intersperses instrumental material between each verse of the chorale.