Cantata 172 must have been one that Bach was especially fond of, since there are records of at least 5 performances during his lifetime, as well as several minor revisions along the way. It dates back to 1714 in Weimar, where it was one the first ones he wrote after being promoted to Konzertmeister and given the responsibility of composing monthly cantatas for the palace church.

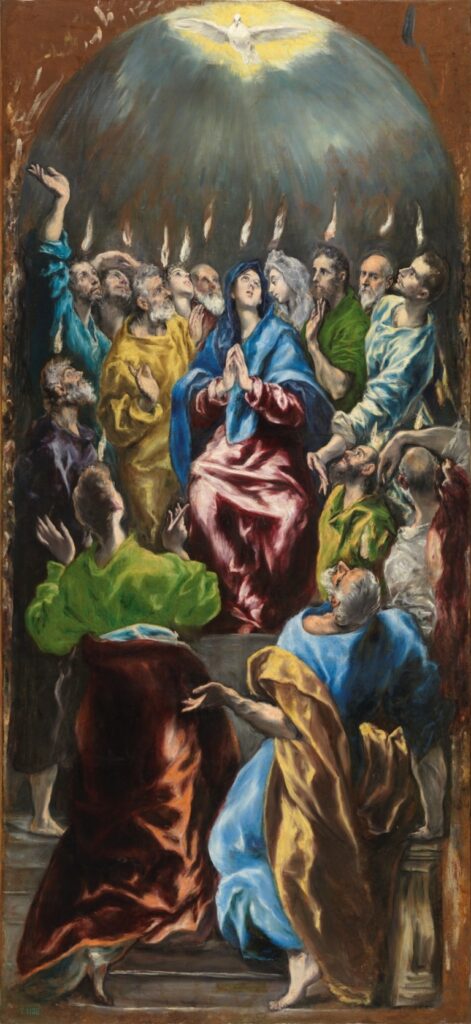

The occasion is the feast of Pentecost (Whit Sunday), and the libretto is most probably by Salomon Franck, although there isn’t complete certainty about this. The Gospel for Pentecost Sunday is John 14: 23-31, and the libretto includes verse 23 literally as its second movement. It also includes, as movement 6, the fourth stanza of Philipp Nicolai’s hymn “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” from 1599, which of course Bach set as a chorale to the famous tune. The rest of the material is madrigalian poetry – the opening chorus and three consecutive arias with no additional recitatives. One of the arias is a duet, a frequent feature in Franck’s librettos, in this case set between the Soul and the Holy Spirit.

The libretto reads as a song of celebration for the coming of the Holy Spirit, and a prayer for it to come into the soul and heart of the believer. Beyond the literal incorporation of verse 23 as the second movement, the other movements elaborate on the concept of God, Jesus and the Spirit (“we”) coming to “live” with the believer. The bass aria makes this explicit by mentioning the Trinity. Throughout the libretto, the soul and heart of the listener are established in different ways as the Spirit’s “home” – the “temple of the soul”, the “hut of our hearts”, the “paradise of the soul”. The tenor aria refers to verse 26 of the Gospel segment, in which Jesus announces the coming of the Holy Spirit. The fifth movement takes the form of a mystical love duet between the soul and the Holy Spirit, and the chorale stanza from Nicolai’s hymn carries forward some of this imagery to conclude.

Given the importance of Pentecost feast, the cantata is scored brilliantly, with 3 trumpets, timpani, oboe, strings, bassoon, 4-part choir, continuo and 4 solo voices. Later revisions (in Leipzig) called for obbligato organ in movement 5, instead of the violoncello and oboe from the Weimar version.

The cantata opens with a festive chorus accompanied by the full orchestra. The trumpets and timpani are set against the strings and reeds for the instrumental ritornello, with the voices forming a third group when they enter, homophonically. The middle section drops the trumpets and presents the voices doubled by the strings in an imitative pattern, first starting from the basses and going up, and then moving down from the sopranos. The movement restarts da-capo.

The second movement is a recitative on the Gospel quote. Since the text consists of Jesus’ speech, it’s set to the bass, as Bach often did. The recitative is secco and turns into an arioso in the final bars for added emphasis. This is the only recitative in the whole piece.

Next are two juxtaposed da-capo arias, similar in structure but contrasting in affect and setting. The first one, an invocation to God and the Holy Trinity, is given to the bass and scored for the 3 trumpets, timpani and a full continuo contingent. The trumpets represent the Trinity, an image also reinforced by the 3 repeated groups of 16th notes in the chords and virtuosic passages of the first trumpet.

The text of the second aria addresses the soul of the believer and prompts it to prepare itself to receive God. The contrast in sonority is remarkable, as this one is given to the tenor and scored for violins and violas in unison, with a flowing melody of continuous eighth notes that illustrates the descent of the Holy Spirit.

The fifth movement is a love dialog between the Soul (soprano) and the Holy Spirit (alto), with an intertwined chorale line on the oboe (which in later revisions of the cantata was given to the organ). The chorale melody comes from Luther’s Pentecost hymn “Komm, Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott” (Come, Holy Spirit, Lord God) from 1524, in a highly ornamented form.

The cantata closes with a chorale on the Philipp Nicolai hymn, set to the “Morgenstern” tune, in which the first violins get an independent part, the second violins double the sopranos, and the violas are divided to double altos and tenors. In Weimar, Bach repeated the opening chorus at the end of the cantata, but it’s likely that he didn’t continue this practice in later Leipzig revisions.