Cantata 182 was performed for the first time in 1714 in Weimar, shortly after Bach was appointed to his post there as Concertmeister. Over the years, Bach reused it possibly up to seven times! There are records of 3 performances in Weimar and 4 in Leipzig which speaks to the appreciation that Bach had for the piece.

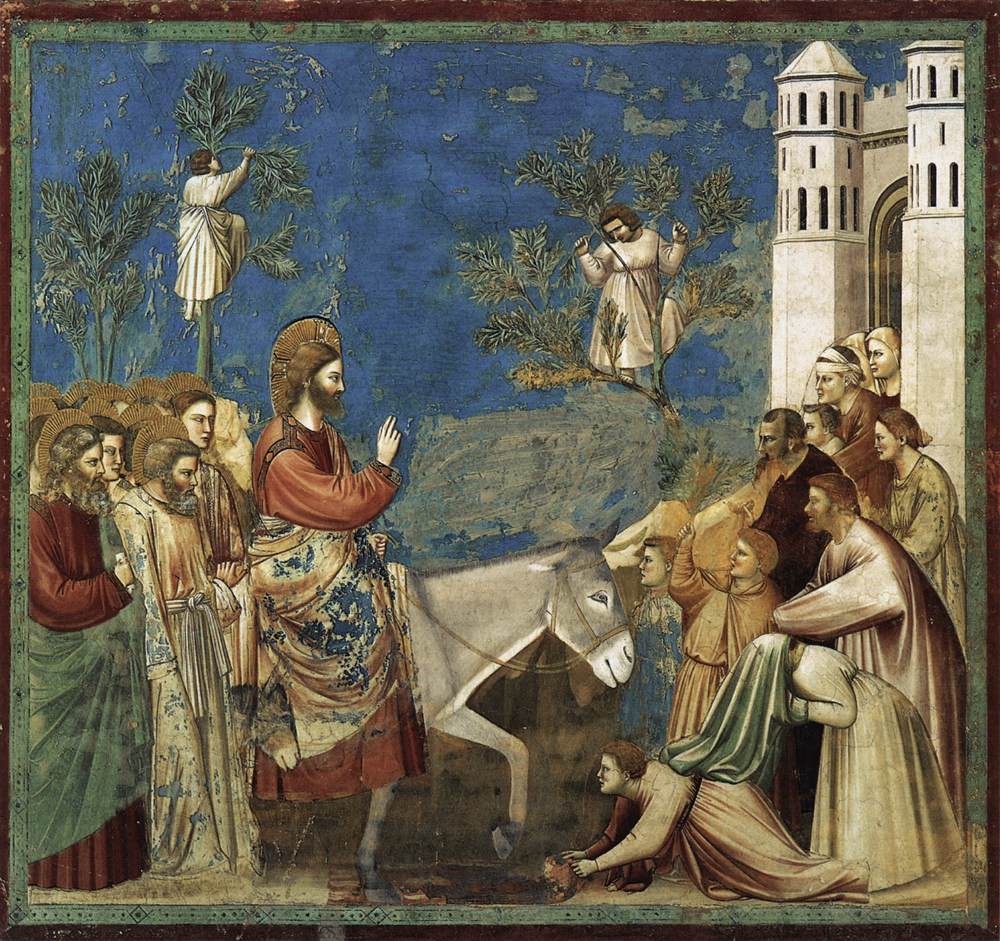

Written for Palm Sunday, its libretto is probably by Salomo Franck, who was the appointed poet at the Weimar court. The text is linked to the Gospel of the day (Matthew 21: 1-9), which depicts the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem riding on a donkey. The reference to Zion in the opening chorus comes from the quote of the prophecy presented in the Gospel text. The scattered mentions of garments, palm branches, and even the choice of the chorale stanza are inspired by the Gospel segment. The text of the bass aria (movement 4) can arguably be linked to the Epistle reading, Philippians 2: 5-11, and the alto aria (movement 5) establishes a parallel between the Christian’s heart and the garments laid down in front of Jesus as he rode into the city. An interesting feature of this libretto, which points to the older German style of cantata, is the absence of poetic recitative – the three arias follow each other with no intervening recitatives.

In its original version, the cantata is scored as a chamber work (recorder, strings, 4 voices and continuo), probably due to the little space available in the Weimar court chapel. Interestingly, there is just one violin line, and two viola lines. A cello is added as a separate part in movements 1, 2, 7 and 8, and is otherwise mentioned as part of the continuo group. Over the years this instrumentation was enriched with the addition of ripieno violins, oboe and a violone for the continuo, to make the piece more suitable for the big churches in Leipzig.

During those early Weimar days, Bach was becoming acquainted with the Italian style, and that influence shows in the cantata in the form of the da capo movements, and solo accompanying instrumental lines which are typical of his early works of this period.

The opening Sonata uses dotted rhythms in the style of a French overture, depicting the ceremonial entry into Jerusalem, with the pizzicato strings suggesting a slowly advancing procession, switching toward the end to “coll’arco” phrases in a nod to the Italian masters. This leads to the opening chorus, a double fugue in “Da capo” form, with a canonic passage as a “B” section which loops around, making the movement end with the homophonic acclamations at the end of part “A”.

The following recitative paraphrases the Gospel with the bass as “Vox Christi”, and it turns into an arioso as the words of the scripture are quoted – “I delight to do your will, my God”.

The following three arias in succession paint Passion-related vignettes in strikingly different moods, suggested by the subjacent ideas in the libretto. The bass aria with string accompaniment (solo violin, two violas and continuo) is animated, in response to the “intense love” and the description of the salvation. The alto aria, featuring the recorder, adopts a slow tempo and sweeping, expressive lines to represent the concept of “bowing down” and “laying down one’s robe” in front of the King. Then, the tenor intervenes with a jarring, poignant response to the crucifixion and the willingness of the believer to join Jesus in “well and woe” (“Wohl und Weh”). This aria is set for voice and continuo only, but the cello plays a significant role with agile movement representing the unrest of the faithful, and the frequent starts-and-stops could be associated to the faltering steps of Jesus bearing the cross. This setting must have been perceived as a striking stylistic departure from the music that the congregation was used to hearing in church in those times.

After the arias, a chorale in two stanzas uses the lower 3 voices to prepare, in quickly moving counterpoint, each entrance of the chorale line in long notes on the soprano. The melody is the “Passion Chorale”, later used by Bach most notably in the St. John Passion, in which it appears 3 times. The lower voices create an intricate warp to support the chorale melody, covering two lines of text at a time.

To close, the final choir brings us back to the sonority of the opening movement. Again in da capo form, a lively dance-like rhythm illustrates “going into Salem”, with the four voices imitating and chasing each other. Bach incorporates some interesting word painting via the shift to minor on the word “Leiden” (“suffering”).