After several weeks of presenting pieces that reused music from pre-Leipzig periods, which allowed Bach to focus his energies on the masterful St. John Passion, Cantata 67 is entirely comprised of new music, composed for the first Sunday after Easter, also known as Quasimodogeniti.

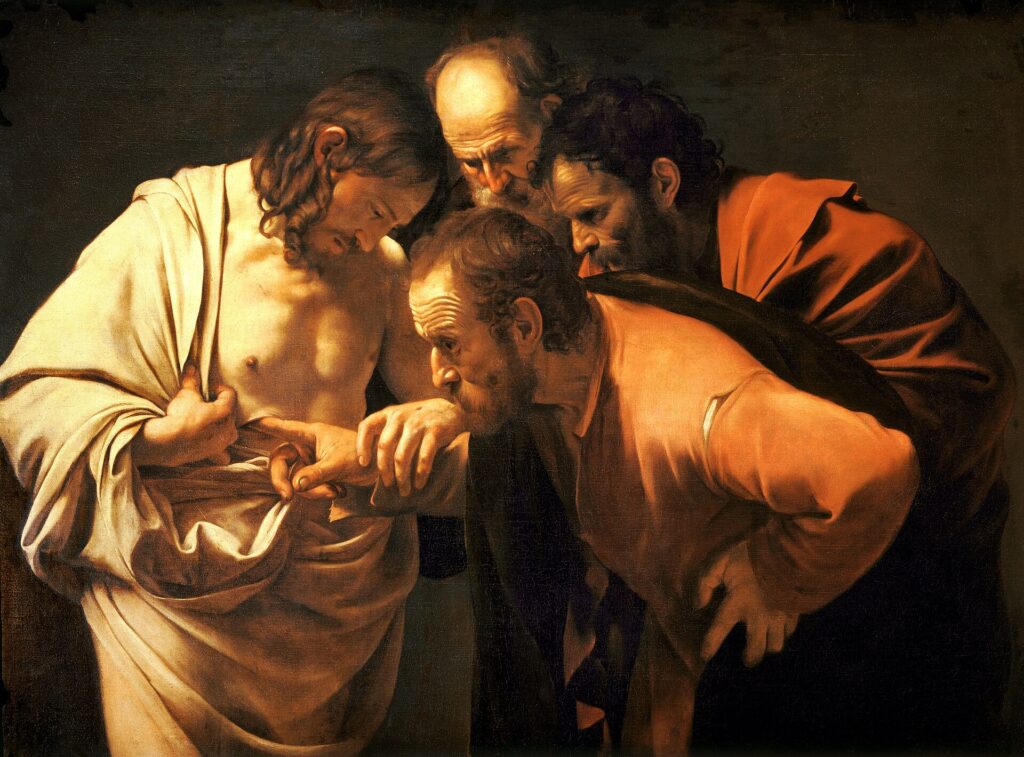

The Gospel for this Sunday is John 20: 19-31, which narrates the appearance of the resurrected Jesus to his disciples, who were locked in a house for fear of persecution after Jesus’ death. In the Gospel narrative, Jesus appears among them, shows them his hands and side, and says “Peace be with you”.

The unknown librettist opens the work with a dictum from 2-Timothy (Paul’s second letter to Timothy) which encourages the reader to remember the resurrection. Movements 2 through 5 (including a chorale integrated as number 4) depict a believer who, in spite of accepting Jesus’ resurrection, is still fearful of their enemies. Movement 6 recreates the scene of Jesus’ appearance; and a stanza of a hymn by Jakob Ebert of 1601, referring to Christ as the “strong helper in need” (“Ein starker Nothelfer”), closes the piece.

The orchestration of the cantata adds a “corno da tirarsi” and, notably, a traverse flute to the more regular oboes d’amore, strings and continuo. The piece calls for a full 4-voice choir, as well as alto, tenor and bass soloists. This is Bach’s first cantata including the traverse flute, an instrument that would become quite frequent during his second yearly cycle.

The cantata opens with a majestic choral fantasia, heralded by the horn with a theme based on the passion chorale “O Lamm Gottes unschuldig”, which is heard repeatedly throughout the movement. Against it, series of eighth notes in ascending runs appear in the oboes first and then in the strings, representing the resurrection. When the choir enters, the imperatives in the text (the dictum from 2-Timothy) are illustrated by repeated chords on the word “Halt” (“keep”) by the lower three voices, while the sopranos take the chorale motif. Shortly after, the texture is lightened as the voices are accompanied by continuo alone, with a new theme similar to the runs of eighths heard before set against the chorale tune stated successively by altos, sopranos and basses. The orchestra then comes back in, and the material continues to be alternated among voices and instruments to close the movement.

The tenor aria takes us into the segment of the cantata that portrays the still-fearful believer. Resembling a gavotte, it’s accompanied by flute and oboe d’amore in unison, strings and continuo. The main theme, stated by the instrumental group and then by the voice, couldn’t be more illustrative of the words, with a rising motif in sixteenths for “erstanden” (“risen”), immediately followed by hesitant, broken up sets of descending notes for “Allein, was schreckt mich noch?”, (“Yet, what still frightens me?”). These two contrasting cells continue their interplay for the entire movement, in all six lines of the musical fabric, as the text doesn’t move past this conflicted state of mind.

The dichotomy of affects represented in the tenor aria is now expanded into a sequence of connected movements: the two alto recitatives and the chorale that they frame, the opening stanza of an Easter hymn by Nikolaus Herman dating back to 1560, which is skillfully blended into the libretto. The first recitative states the Christian’s lingering fears using strong language and imagery, and the affirmative chorale, irrupting in bright major mode and triple meter, serves as reassurance and consolation. In the next recitative, the alto first continues to express doubt and restlessness, then articulates a request for support in the fight against one’s enemies, and finally expresses faith in that forthcoming help.

The striking sixth movement depicts the scene of Jesus’ appearance to his disciples in the locked house. Bach utilizes the full orchestra, plus the choir’s sopranos, altos and tenors to represent the disciples (or the community of Christians) while the solo bass impersonates Jesus. The strings open with a frantic passage of sixteenth notes, punctuated by runs of thirty-seconds, originating from the concepts of fear, rage and battle that percolate the libretto so far. However, it’s set in major mode, which lends the passage a feeling of optimism and hope – a hint of what’s about to happen. This section transitions seamlessly into the first of four interventions by Jesus, uttering the words from the Gospel story, “Peace be with you”. The wind instruments accompany Jesus with a calm, rocking motif of dotted eighths and sixteenth in a triple meter. The upper choir’s voices react to Jesus’s presence with joy and newfound poise against their enemies, backed by the energetic strings, whose theme we now perceive as excitement. This alternation between Jesus and disciples is repeated three times and, for Jesus’ last intervention, the strings join the winds on their calm, peaceful motif.

The cantata ends in bright A major, with the Ebert chorale set to four-part harmony.